Could TSLA Be The Next NFLX? (Part 0)

Commoditizing moats doesn’t have to imply extinction — it could simply mean becoming the next Nestlé.

TSLA ‘24 vs. NFLX ‘22: Cyclical Similarities Table of Contents: 1. Industry Commoditization from Business Model Disruption - Largest incumbent in commodifying industry - Cycles Always Recycle - TSLA's recent business woes 2. More Similarities Than You’d Think - The Disruptor - Capital-intensive businesses - Enormous competition from global incumbents - Cleared "relevance window" by a whisker - Near-total commoditization of Auto & Media sectors - Top dogs of their newly disrupted industries 3. Similarly Optimistic Forward-Looking Outlook? - Market share leader of US EV industry - Cost leadership - First-mover advantage - Economies of scale - DTC Distribution “Moat” 5. 🧠 AI-generated summary (scroll to bottom of this report)

“Every once in a while, an up-or-down-leg goes on for a long time and/or to a great extreme and people start to say "this time it's different." They cite the changes in geopolitics, institutions, technology or behavior that have rendered the "old rules" obsolete. They make investment decisions that extrapolate the recent trend. And then it turns out that the old rules still apply and the Cycle resumes. In the end, trees don't grow to the sky, and few things go to zero.” ― Howard Marks, The Most Important Thing

Read my follow-up TSLA articles:

TSLA ‘24 vs. NFLX ‘22: Cyclical Similarities

In May ‘22, all was lost for NFLX. Bill Ackman had sold his entire NFLX stake at a loss after holding it for a mere three months, and their share price had fallen by nearly -70% YTD. There was plenty of doom and gloom about its subscription-only business model being disrupted, amidst the streaming giant’s sudden and unexpected shift towards an ad-supported business model.

This is somewhat akin to the extremely negative sentiment that TSLA is currently battling amidst increasing competition, namely from Chinese EVs.

However, NFLX has gone on to post some of its best results contrary to popular expectations — with its valuation climbing by 250% since then. While the role of favorable macro policy should be emphasized in their massive valuation hike, the fact is that Netflix’s business remains robust — business model disruption notwithstanding. As I’ve painstakingly described in my earlier Disney reports, the US Media industry is likely to consolidate into just two oligopolistic players — NFLX and DIS.

I am seeing very similar patterns between NFLX ‘22 and TSLA today amidst recent developments in the US Auto industry. Think about it:

Both are (currently) leaders in their respective commoditized sectors.

Both have had to entertain severe business model disruptions — from possessing structural moats to gradually commodifying businesses (i.e. “melting ice cube”).

Relative to competitors, both have had to pivot from leaning on their superior products to squeezing out margins from lower-cost business processes resulting from greater economies of scale (manufacturing in TSLA’s case, distribution in NFLX’s case).

Both of their respective businesses are suffering from price wars. (i.e. commoditized sector)

Both were/are respectively perceived as facing extended levels of competitive threats to their businesses.

Both have had careening share prices in the face of negative market sentiment.

We’ll dive into each point deeper below, but the parallels between NFLX ‘22 and TSLA ‘24 are unmistakable.

This observation also leans into a highly established first principle of value investing — the phenomenon of CYCLES, a Howard Marks classic as detailed in his bestselling book The Most Important Thing.

Subscribers to the concept of industry cycles would have recognized that NFLX ‘22 looked like a stereotypical sector incumbent in a commoditized sector, where economies of scale and branding rule supreme. In 2022, NFLX had both; and TSLA has both today as well.

Industry downcycles — like the one facing Netflix in 2022 and Tesla today — also tend to be highly favorable towards sector incumbents in commoditized sectors, typically owing to their high FCF and excess scale — as it allows them to survive longer and partake in excess opportunities and gain market share, while their smaller competitors bleed to death. In retrospect, this has also been a great way to describe NFLX’s journey from mid-2022 to today.

TSLA still has a whole lot of TAM to grow into — intense competition notwithstanding. This sets the stage for an interesting possibility — given its massive headstart in the US EV industry today, could we expect TSLA to simply grow into the largest mainstream US auto company? Drawing a parallel to Netflix’s recent meteoric rise, losing your moats doesn’t have to imply extinction — on the contrary, it could simply mean becoming the next Nestlé.

This sets the context for TSLA also possibly being at the beginning of that same painful journey as NFLX was in mid-2022 — where it might be able to emerge stronger than ever following the inevitable inflection of that cycle. Or to describe it in lesser words:

“Could TSLA Be The Next NFLX?”

Disclaimer: The contents of this document are NOT meant to serve as investment advice. Read our full disclaimers below:TSLA ‘24 vs. NFLX ‘22

Industry Commoditization from Business Model Disruption

In this section:

1. Largest incumbent in commodifying industry

2. Cycles Always Recycle

3. TSLA's recent business woes

In mid-2022, the talk of town was that NFLX’s future in the Streaming industry was over. It had just announced a shift to a partially ad-supported business model, which was taken by markets to mean an admission of weakness amidst their decade-long subscription-only business model. This was something that was considered somewhat of a moat in the relatively novel streaming industry.

However, astute Media industry analysts who were familiar with how the legacy Cable sector disrupted the preceding Broadcast/Satellite industry during the time of John Malone could see many parallels to the shift that was taking place in the Streaming sector at the time:

Firstly, rather than interpreting the commoditization of the Streaming sector as an extinction event, they would have recognized that Netflix was by far the largest incumbent in a commodifying industry — where it’s huge branding presence and excess economies of scale gave it a leg-up over competitors.

Secondly, the recognition of how Cycles Always Recycle implied that industry demand:supply would eventually inflect upwards at some point — putting NFLX in a great position to “vulturize” market share from smaller competitors who were bleeding cash flows.

This prescient observation has since largely played out according to expectations. While monetary policy has undoubtedly provided a lift to NFLX’s valuations, it is also indubitably true that Netflix’s underlying fundamentals have only gained in strength since then vis-a-vis competitors like Disney+. NFLX 0.00%↑ share price increase of 250% belies investor confidence behind its competitive advantages, its business model disruption notwithstanding.

Astute Auto industry analysts will also recognize the surprising number of parallels that exist between NFLX’s market narratives in 2022 and TSLA today.

As correctly predicted by early TSLA bears, the EV company has finally revealed its true nature as a capital-intensive automotive business, as compared to the capital-light Tech business Musk had been trying to present it as.

It is currently facing many relatable financial woes as a result, namely the relatively commoditized nature of the EV business in the hyper-competitive auto industry — which has recently necessitated price cuts to the Model 3/Y in order to maintain deliveries and production. It’s important for TSLA to maintain its high production levels, as Tesla’s unit costs are largely a function of high utilization rates at their capital-intensive Gigafactories.

On top of that, Musk has also made the Shanghai Gigafactory a cornerstone of Tesla’s success. The idea was to massively scale up Tesla’s ability to churn out EV frames using its Gigapresses — and exploit the labor differential and bill-of-materials (BoM) differential between China and the US to save on unit costs, while still being able to generate export sales to Western markets.

This narrative has collapsed in the face of China’s recent economic woes, as well as recent regulatory fears over Chinese EV imports potentially being banned in both the US and EU.

But wait, there’s more.

Since Tesla announced Giga Shanghai in early-2019, its Chinese EV competitors have since caught up to it in terms of Gigapress technology. Gigapresses can reduce manufacturing unit costs by up to 40% (at the expense of higher operating leverage) because they stamp out the entire EV frame in one go — as opposed to the traditional method of stamping out twelve separate pieces, and then stitching them together.

Given how the Gigapress was Tesla’s proprietary invention and was supposed to be Tesla’s single most important manufacturing USP in the face of a commoditizing EV business model, this development has further eroded its competitive advantage vis-a-vis global auto brands. And while this was all but inevitable, it does no favors to TSLA to have its one remaining structural cost advantage copied so rapidly.

TSLA ‘24 vs. NFLX ‘22

More Similarities Than You’d Think

1. The Disruptor

2. Capital-intensive businesses

3. Enormous competition from global incumbents

4. Cleared "relevance window" by a whisker

5. Near-total commoditization of Auto & Media sectors

6. Top dogs of their newly disrupted industries

Given TSLA’s disruption context as described above, the similarities to NFLX’s own disruption story becomes more apparent.

First, both Netflix’s and Tesla’s role in their respective markets are the Disruptor. They were both beneficiaries of a decade of loose monetary policy, which enabled them to fund their enormously capital-intensive enterprises at relatively low rates of return for extended periods of time. Both were able to capitalize on this capital advantage by leaning on the technological advantage in their respective industries to leapfrog established incumbents amidst a rapidly shifting industry landscape.

Second, these are both highly capital-intensive businesses, their Tech sector designations notwithstanding. As I’ve described in my Disney reports, NFLX initially had to address its lack of hit original programming by building out its own content library — which involved the highly uncertain and capital-intensive process of creating new hit shows. Similarly, TSLA actually needs to manufacture high volumes of physical automobiles, and build out an actual full-fledged factory in order to do that.

Third, Tesla is now facing enormous competition by large global auto brands — similarly to how the narrative for Netflix in 2022 was that it was facing large and well-funded global Media titans. These are truly Big Business Battlegrounds, consisting of incredibly large auto conglomerates each owning dozens of marques under their wing to tackle all possible addressable markets, and having decades of experience over the young disruptor. Netflix was until recently in a similarly precarious position, possessing relatively few hit original programming of its own and arguably still behind on its library of hit content to this day.

Fourth, both also took enormous risks and managed to clear the “relevance window” by a whisker, attaining the critical mass (i.e. economies of scale) necessary in order to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with their large, legacy competitors just in the nick of time before they could be nudged off the ledge.

In Netflix’s case, they managed to build out enough critical mass in their content library just in time; right before Disney+ came storming out the gates in pursuit of their market share. It’s worth remembering that Netflix didn’t start out with their own library of hit content — instead, they relied on very long-term syndication rights to show hit media IP belonging to other media incumbents on their platform (e.g. Friends). As the Netflix threat grew, these incumbents progressively withdrew these syndication rights, withholding Netflix’s ability to remain competitive from a content library standpoint. Luckily, Netflix was able to build out its own library of hit original programming (i.e. critical mass) just in time before the Disney+ threat beared down on them.

Meanwhile, Tesla also managed to clear its own industry’s “relevance window” by a whisker — apparently flirting with bankruptcy several times in the process. Using its now-famous laddered approach to selling progressively cheaper EVs to a captive audience, the company was able to generate enough cash flow in stages to fund the incredibly expensive build out of its Gigafactories — a never-before tried assembly line process in the auto industry. This was a similarly ludicrously cash burning exercise which required the young EV upstart to attain the critical mass necessary to compete with sector incumbents. Luckily, the pandemic-era subsidies and irrational exuberance for all things Tech/Green Energy gave TSLA the final boost it needed to clear the hurdles of minimum viable economies of scale — allowing it to leapfrog its large competitors just in the nick of time before the latter became relevant in EVs.

Fifth, both the Media and Auto industries which Netflix and Tesla occupy respectively have developed very similarly — by virtue of the near-total commoditization of both industries. As aforementioned, both started out as disruptors in a shifting industry landscape, with their main competitive advantage being characterized as having a superior product. As the industry disruption completed and incumbents adapted to the new normal, the competitive factor in both industries shifted towards gaining unit cost advantages via economies of scale. For Netflix, this meant leaning on its leading economies of scale to negotiate better media terms with other industry participants; while for Tesla, this manifested as gaining a manufacturing cost advantage by virtue of their Gigapresses. Almost every other business process has since become commoditized, with the final point of differentiations being price — and perhaps their respective brands.

Lastly, both Netflix and Tesla have managed to emerge as the top dogs of their respective newly disrupted industries. This is important in the context of both industries being commoditized, as it gives them the necessary economies of scale to bully competitors into submission — usually in the form of lower prices. While Tesla’s journey here is far from over, Netflix’s end seems to increasingly visible. And if previous industry cycles serve as any clue, both of their newfound sector incumbencies will go a long way towards enabling further entrenchment within their respective industries — simply by virtue of being able to drive unit costs down more than their competitors can.

TSLA ‘24 vs. NFLX ‘22

Similarly Optimistic Forward-Looking Outlook?

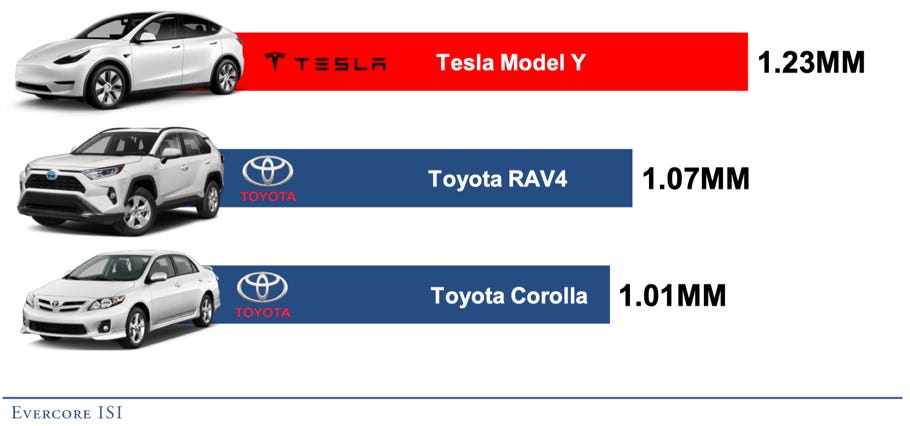

1. Market share leader of US EV industry

2. Cost leadership

3. First-mover advantage

4. Economies of scale

5. DTC Distribution “Moat”With the latest news about TSLA cutting 10% of its global workforce and two key executives leaving, the pessimism around the EV leader has to be acknowledged. However, I wouldn’t say that the doom and gloom surrounding TSLA today is any worse than it was around NFLX or even META amidst their troughs in 2022 — at least Bill Ackman isn’t selling.

If you were to ask me what business factors could potentially contribute towards TSLA’s business future mimicking that of NFLX’s optimistic trajectory over the past two years, here’s what I can think of:

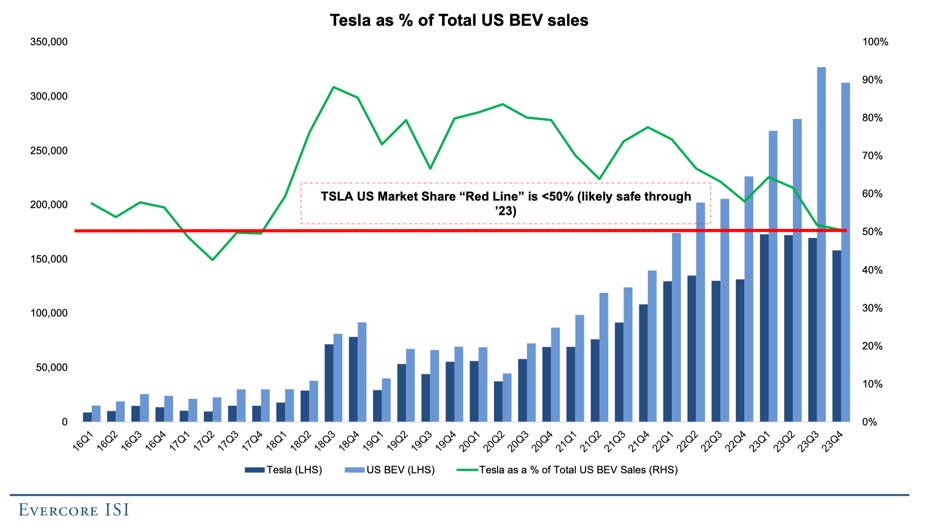

Market share leader of US EV industry: Gives it brand and scale advantages. It may not be so at the global level, but it would seem that US and EU protectionist policy might help ward off market share grabs by Chinese EV companies.

Cost leadership: US competitors may be catching up with the Gigapresses, but most of them are still only in the exploratory stage. TSLA took a lot of upfront risks when they first implemented the untested technology — but now that they’re past the learning curve, its US competitors are somewhat lagging behind it and still need to pass through that same learning curve. This is similar to how the rest of the Media industry is still somewhat behind Netflix and Disney+ on streaming, and are in the midst of the painfully costly learning curve involved in transitioning to DTC.

First-mover advantage: TSLA remains the largest BEV seller in the US by far, with still over 50% market share. The difference between US NEV and BEV sales are immaterial1.

Economies of scale: TSLA remains by far the largest seller of any single EV model in the world, as most of their sales are concentrated in just two models: The Model 3/Y. This high level of manufacturing concentration gives them industry-leading gross margins of 20%, far over the wider auto industry average GM of 7.5%2 with a vastly more diverse SKU base.

DTC Distribution “Moat”: In NFLX’s case, they had a huge advantage over its Cable incumbent competitors in terms of mastering the distribution of media over Internet fiber, which includes overcoming the expensive and necessary technological logistical hurdles to do so well. TSLA on the other hand bypasses dealerships and sells their cars via direct-sales. Both result in having a cost advantage over their competitors.

To be clear, I’m not trying to suggest that TSLA is going to come out of its current debacle as positively as NFLX has. However, one finds it hard to deny the stark number of industry-based similarities between NFLX ‘22 and TSLA today.

I’ll be doing a series of TSLA articles over the next few weeks, which will also serve as an EV industry primer. At the end of this series of TSLA reports, you will have gathered a sufficiently robust understanding of all of TSLA’s moving parts, so as to be able to discern TSLA’s fair value for yourself — whether you agree with my valuation or not.

🧠 AI-Generated Summary

Claude

TSLA and NFLX share striking parallels in their journeys as disruptors facing the challenges of industry commoditization and intense competition. In 2022, NFLX's transition to a partially ad-supported model signaled the commoditization of the streaming industry, but the company leveraged its scale and brand to maintain a competitive edge. Similarly, TSLA, now recognized as a capital-intensive automotive company rather than a tech firm, grapples with the commoditization of the EV sector, necessitating strategic price adjustments and high utilization of Gigafactories to optimize cost efficiency.

Both companies benefited from an era of loose monetary policies, enabling them to undertake capital-intensive expansions and technological advancements that outpaced incumbents. As their respective industries faced near-total commoditization, TSLA and NFLX pivoted to focus on economies of scale and cost leadership to establish market dominance. However, TSLA's once-proprietary Gigapress technology has been replicated by Chinese EV competitors, eroding its manufacturing advantage.

Despite these challenges, TSLA maintains a strong position in the US EV market, boasting significant market share, cost leadership, and first-mover advantages. The company's concentrated production in the Model 3/Y allows for economies of scale, while its direct-to-consumer distribution model bypasses traditional dealerships, mirroring NFLX's advantage in mastering online content delivery.

The TSLA-NFLX comparison highlights the critical importance of scale, brand power, and strategic adaptation in maintaining industry leadership amidst the pressures of commoditization and competition. As these companies navigate their respective challenges, their ability to leverage these key factors will likely determine their long-term success in shaping the future of their industries.

GPT-4

TSLA and NFLX share parallels in disruption, facing commoditization and intense competition within their respective industries.

NFLX transitioned to a partially ad-supported model in 2022, signaling industry commoditization but leveraging scale and brand for competitive advantage.

TSLA, identified as a capital-intensive automotive rather than a tech company, faces commoditization in the EV sector, necessitating strategic price adjustments and high utilization of Gigafactories for cost efficiency.

Both companies benefited from loose monetary policies, enabling capital-intensive expansions and technological advancements to outpace incumbents.

TSLA and NFLX faced near-total commoditization of their sectors, pivoting to economies of scale and cost leadership for market dominance.

TSLA's Gigapress technology, a manufacturing USP, has been replicated by Chinese EV competitors, diluting its competitive advantage.

Despite challenges, TSLA retains significant market share, cost leadership, and first-mover advantages in the US EV market, supported by economies of scale and a direct-to-consumer distribution model.

The comparison underscores the importance of scale, brand, and strategic adaptation in maintaining industry leadership amidst commoditization and competitive pressures.

Check out our previous stock reports:

Disclaimer: This document does not in any way constitute an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any investment, security, or commodity discussed herein or of any of the authors. To the best of the authors’ abilities and beliefs, all information contained herein is accurate and reliable. The authors may hold or be short any shares or derivative positions in any company discussed in this document at any time, and may benefit from any change in the valuation of any other companies, securities, or commodities discussed in this document. The content of this document is not intended to constitute individual investment advice, and are merely the personal views of the author which may be subject to change without notice. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks, and readers are advised to consult with their financial advisor before taking any action pertaining to the contents of this document. The information contained in this document may include, or incorporate by reference, forward-looking statements, which would include any statements that are not statements of historical fact. Any or all forward-looking assumptions, expectations, projections, intentions or beliefs about future events may turn out to be wrong. These forward-looking statements can be affected by inaccurate assumptions or by known or unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, most of which are beyond the authors’ control. Investors should conduct independent due diligence, with assistance from professional financial, legal and tax experts, on all securities, companies, and commodities discussed in this document and develop a stand-alone judgment of the relevant markets prior to making any investment decision.AI: The spread between US Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV) and New Energy Vehicle (NEV) sales is a critical metric to gauge EV adoption. In the US, NEVs encompass BEVs, Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs), and Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs). However, BEVs constitute the lion's share of NEV sales. Per latest data, BEVs accounted for 807,180 units or 5.8% of total US light vehicle sales in 2022. In stark contrast, PHEV sales stood at a mere 176,420 units or 20% of total NEV sales. FCEV volumes were negligible. Ergo, the delta between BEV and NEV sales is slim, with BEVs commanding a whopping 80%+ share of the NEV mix. This underscores the dominance of pure-play BEVs in the US NEV landscape. Key takeaway: The US NEV narrative is essentially a BEV story, with a razor-thin spread between the two categories. As BEVs accelerate their market penetration, expect this gap to contract further in the medium-term.

In contrast, the fledgling EV industry’s GMs are still all over the place, as compared to traditional auto industry GMs.